Chapter 4 Relativism

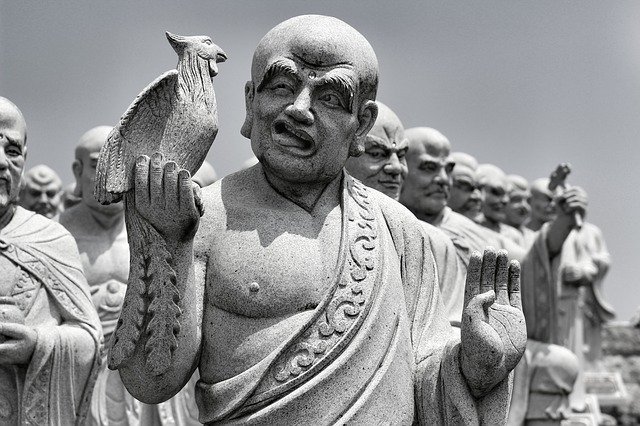

mikhsan at pixabay.com

As we now turn to look more carefully at ethics it may help to have a sense of the general approach we will be following here. We’ll be looking at a variety of theoretical perspectives on ethics – perspectives which determine the position one might take regarding questions such as:

- Is ethics just a matter of opinion, or is can ethical principles lay claim to a more universal validity?

- What is the relation between ethics, law and religion – all of these spell out rules for behavior but on the basis of what and what happens when they come into conflict?

- Is it rational to be ethical or does ethics depend on something other than our ability to think things through?

- Is there anything that is just plain wrong, no matter what the consequences?

There are many possible ways to consider these questions. I’ll be following a fairly common approach that looks at them in the light of various general theories or philosophical positions one might adopt. Each of these theories makes a particular claim about what is fundamental to ethics, highlights certain aspects of our ethical lives and also provides some guidance for dealing with ethical controversies in the real world. These theories have all found both defenders and critics in the history of philosophy although here I will be more concerned with them as general approaches to ethics than with worrying too much about accurately presenting the views of historical thinkers. These theories as I am presenting them can best be looked at as “ideal types” that have their own inner logic, and their own strengths and weaknesses as attempts to articulate and defend some version of what ethics is really all about.

In my view not all of these theories are equally viable. In fact it seems to me that most of them simply fail as approaches to ethics for a variety of reasons that will become clearer in each case. This brings up the obvious question of why we should bother looking at a whole slew of approaches to ethics that ultimately don’t work instead of just more directly articulating one that does. There are two reasons to take this approach. First, in spite of the difficulties faced by these approaches to ethics, all of them continue to be popular and find defenders both historically and at the present. Even if these defenses are inadequate, they still have and have had their champions. There is a version of an old joke about anarchists that applies here to philosophers: given three philosophers in a room together there will be four positions taken by them on any topic that comes up for discussion. This is a feature and not a bug of philosophy, since philosophy is the attempt to articulate and defend a general account of such abstract topics as the nature of reality, knowledge and values, so the more particular positions we can examine the better. Just like in science we should welcome a diversity of approaches rather than rule any out at the start. But unlike in science, unworkable philosophical theories have a longer shelf life since the cost for holding on to them is relatively easy to bear. If a scientific theory is fatally flawed that is typically clear – one’s prediction of what the experiments or data will show fails, other explanations cover more cases with fewer assumptions and better fit with the data, the bridge built on the basis of one’s calculations collapses. The cost of bad science is steep. In philosophy, however, the costs of holding onto unsuccessful theories is having to put up with theoretical incoherence, to be willing to hold conflicting views in the mind at the same time. And it turns out that us humans are pretty good at doing these things – all you have to do to live with a poorly worked out set of fundamental beliefs is stop thinking about them.

The second reason for considering a multitude of unsuccessful approaches to ethics here is that each of these approaches does have the advantage of focusing on some important aspect of ethics. To the extent that these theories fail it is because they tend to overemphasize the aspect in question and ignore others. Looking at a variety of approaches can thus help give us a clearer picture of what ethics as a whole is all about, even in the absence of some final master theory that would unify ethics once and for all and win universal assent. It seems to me that there is a certain “logic” to the story I’ll be telling here, even if it is nothing like a necessary development, a magical dialectical unfolding of the Truth about ethics, but I do present each theory as an effort to take in to account the failings of the proceeding accounts. Making sense of our ethical lives and thinking clearly about ethics is hard, but it seems to me that it is worth the effort. Philosophical ethics may not be an empirical science, and debates in ethics may not ever be resolved, but it is a rich field well worth exploring. My presentation here is intended in the spirit of a guidebook, pointing out certain general features of the landscape, some important landmarks and major hazards to be reckoned with.

So much for a general account of what we will be up to here. This section of the text looks at two approaches to ethics that may seem to be diametrically opposed – cultural relativism and the attempt to show how ethics can and should be based on religion. According to cultural relativism, ethical rules and norms are determined by culture in the sense that there are no absolute and universal rules with an independent warrant, but only particular, culturally determined ways of conducting oneself, none fundamentally better or worse than the others. According to religious approaches to ethics, ethical rules and principles do have an absolute foundation and that foundation is to be found is an authoritative set of religious truths. In spite of their obvious opposition, with relativism denying the existence of ethical absolutes and religious approaches affirming it, in a sense both have something essential in common, which is the idea that ethical rules come to us “from outside” and have little to do with human choices. Their opposition lies in whether or not the source of ethical rules varies from place to place or not. Both of these approaches will be found wanting, for roughly parallel reasons. And so the next part of the text, which examines various more purely philosophical approaches to ethics, takes up the question of what ethics might look like if it is something we humans create and not imposed from outside by culture, God or human nature.

A note on method:

In this text I’ll be exploring various approaches to ethics chiefly as I understand them. Although at times I make reference to historical philosophers and sometimes to their particular arguments and texts, this book is not intended as a contribution to historical scholarship. Instead my approach is to consider ethics in terms of a series of “ideal types” which, while they may overlap with the ideas of certain historical figures, are intended to capture what I understand to be the major lines of argument available to anyone who attempts to clarify basic notions of ethics. There is a certain inner logic it seems to me to how we can, and maybe even should, think about ethics. Or maybe that is just a result of my having spent too much time reading Hegel in my youth. In either case, caveat lector – let the reader beware.

Over time I will also try to expand on and/or make room for approaches I haven’t yet had time to integrate into my overall scheme, such as virtue ethics, Buddhist ethics (and non-Western approaches more broadly) and feminist approaches to ethics. I do welcome suggestions about how to extend and revise this text to make it more inclusive.